Introduction

In 2010, I decided to begin making the transition from business-as-usual to a low-carbon, sustainable existence, to try to mitigate my personal contribution to climate change, to be part of the solution and one less part of the problem. This case-study documents what can be achieved in an average UK 1960’s three-bedroom semi-detached house, with a modern but low-impact lifestyle. What follows is a summary of what has been achieved through the activities which can be influenced individually from 2010 to 2024, the second successive year in which Net-zero Carbon was achieved. The full time-line diary with more detail can be viewed in the accompanying text ‘The Road to Carbon-zero,’ on the right-side menu.

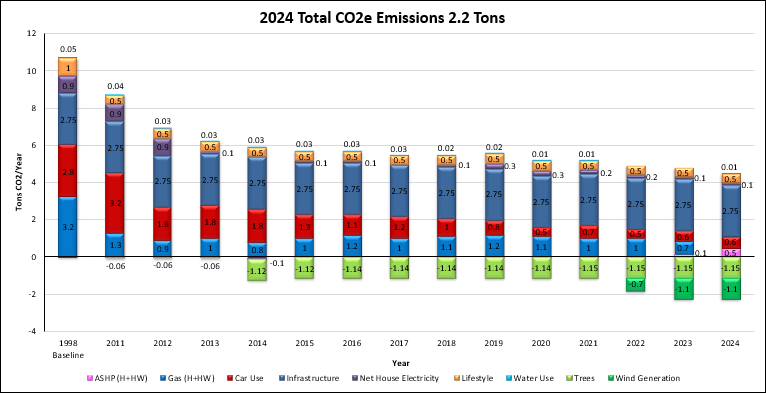

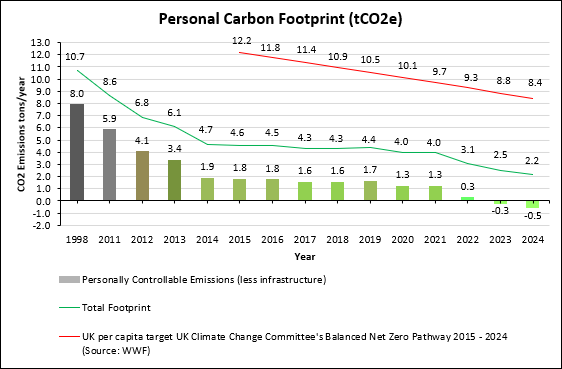

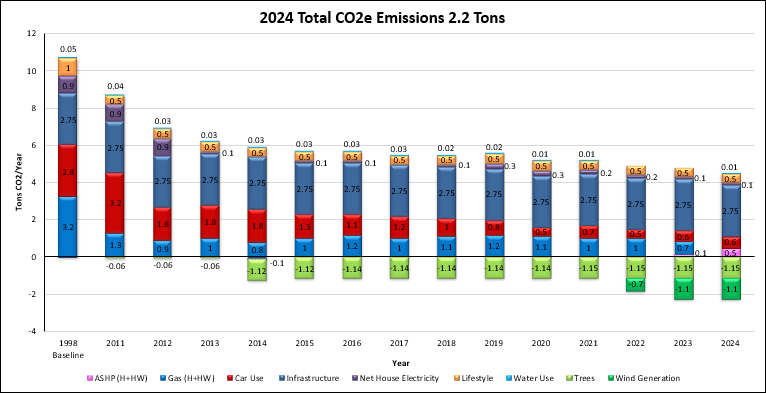

Overall, by 2024 total carbon emissions have been reduced by 79% or 8.5 tCO2e per year compared to the 1998 baseline year, from 10.7 tCO2e to 2.2 tCO2e. For context, this is less than a 2030 global per-capita footprint target aligned with the Paris Agreement somewhere in the region of 2.3 tCO2e (WWF, 2023). Furthermore, personally controllable emissions, omitting infrastructure, produced a carbon negative figure of -0.5 tCO2e per year. The chart in Fig.1. shows the carbon emissions reduction over the period, comparing the total footprint, personally controllable emissions, and the UK per capita target according to The World-Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) carbon footprint calculator. This calculator also suggests the average carbon footprint for my area is 11.3 tCO2e per person.

(Note: The methods used here are just one interpretation of calculating CO2 emissions, it is not exhaustive, it is a general simplification for illustrative purposes).

Fig.1. The footprint of Annual CO2e emissions from 2011 to 2024, and including the 1998 baseline.

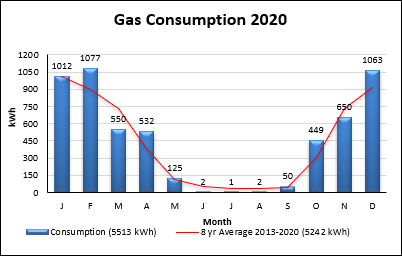

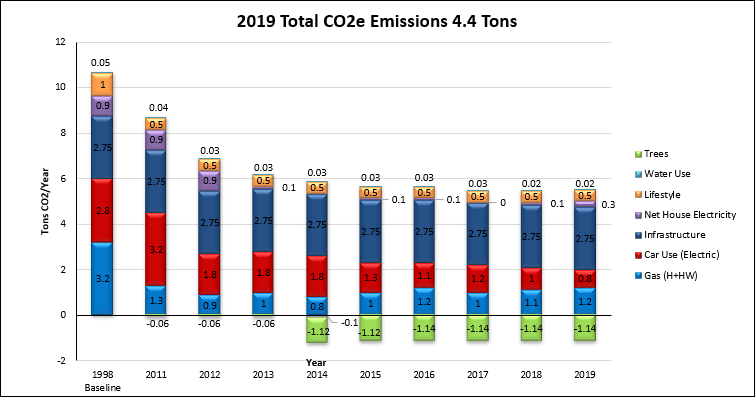

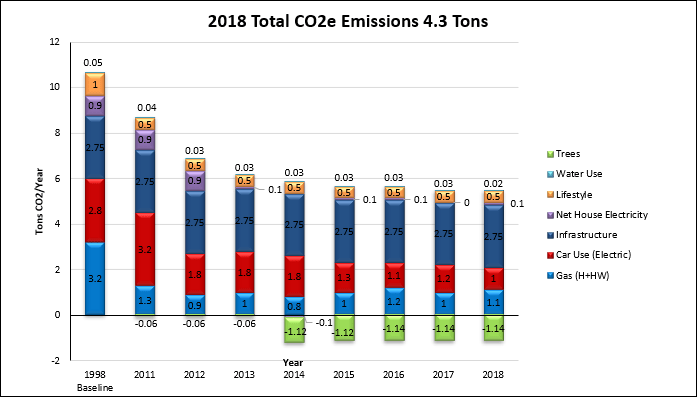

The chart in Fig.2. shows the Carbon Fingerprint, which shows the emission impact over the period from the individual activities which can be targeted for reduction.

Fig.2. The fingerprint of Annual CO2e emissions from 2011 to 2024, and including the 1998 baseline. (Note: Car Use is electric from 2015 – 2024).

Summary of Impacts – 2024 compared to 1998 Baseline year

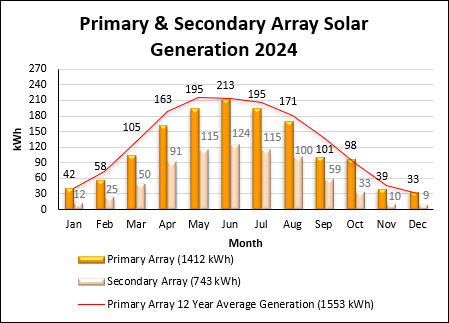

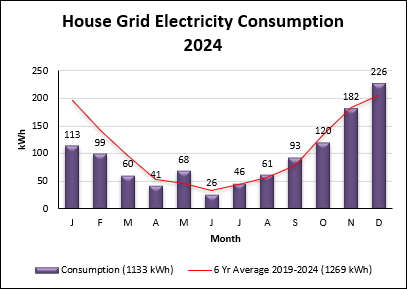

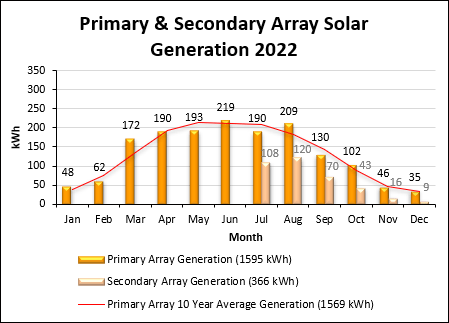

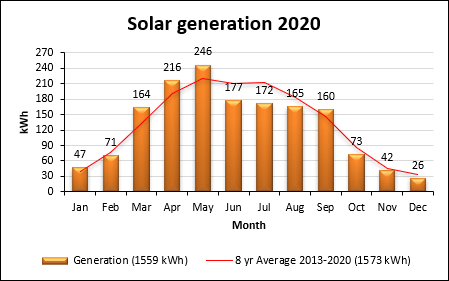

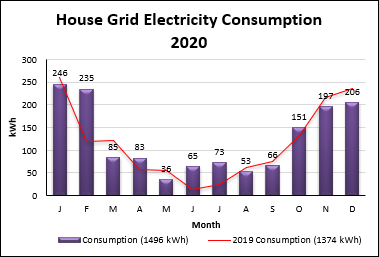

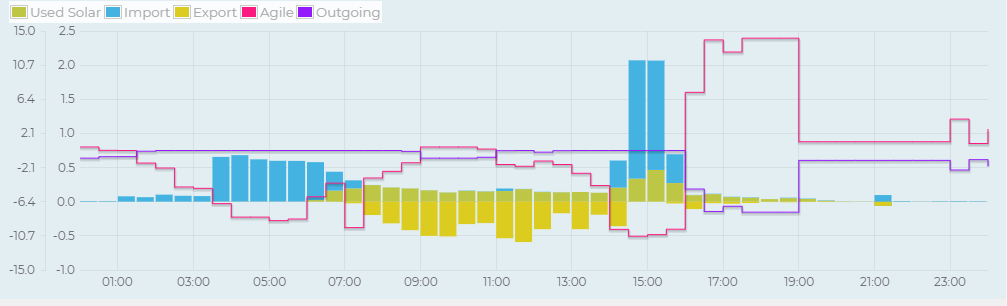

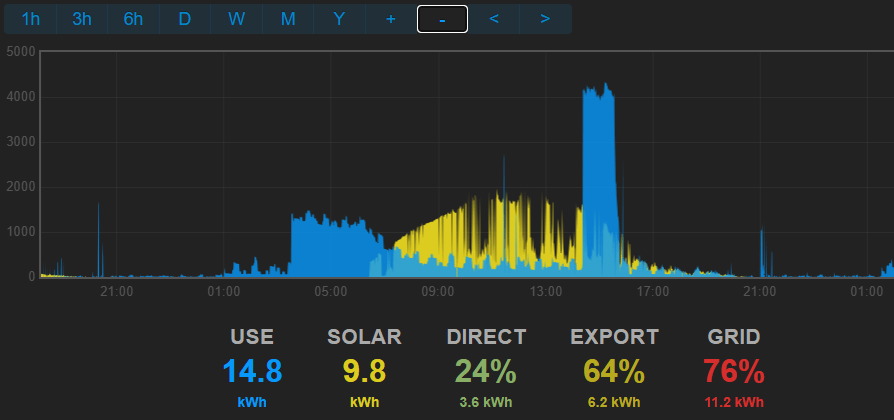

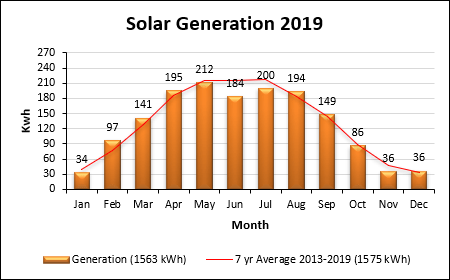

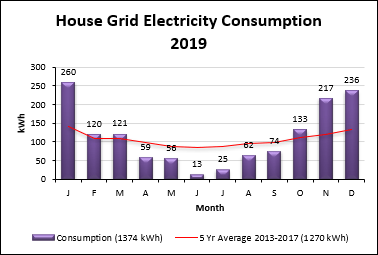

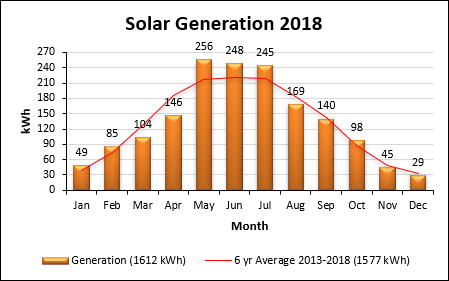

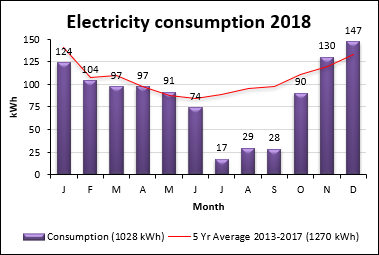

Annual Household Grid Electricity Energy Consumption reduced by 34%, emissions reduced by 0.8 tCO2e/Year, through efficiency and solar power used on-site and exported to the National Grid. Energy storage battery provides load shifting from peak-time to off-peak.

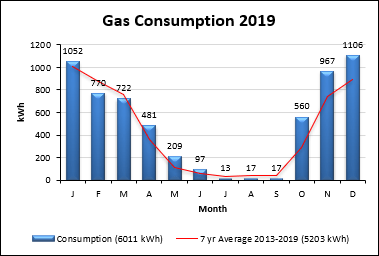

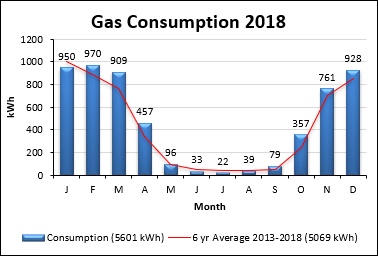

Annual Space and Water Heating Energy Consumption reduced by 84%, emissions reduced by 2.7 tCO2e/Year, through insulation, improved glazing, and more efficient heat sources, initially gas condensing boiler then Air Source Heat Pump.

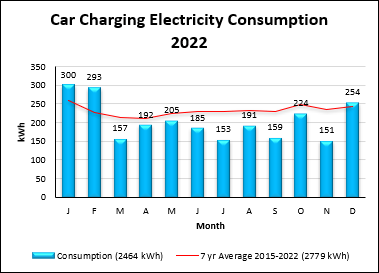

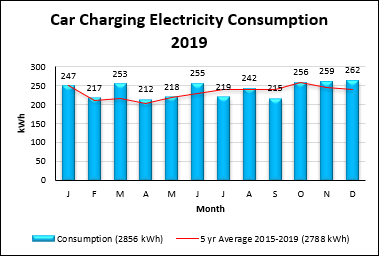

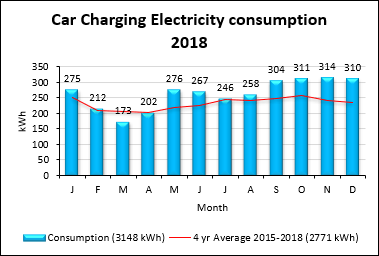

Annual Car Travel emissions reduced by 79% or 2.2 tCO2e/Year through switching from Internal Combustion Engine to Battery Electric power, despite an average increase in mileage of 4000 mile/Year.

Annual Water Consumption reduced by 80%, emissions reduced by 0.04 tCO2e/Year through water harvesting, water efficient appliances, and only using a shower.

Annual Lifestyle emissions reduced by 50% or 0.5 tCO2e/Year through low consumption lifestyle, local and sustainably sourced organic food, a vegan diet, support for several environmental charities, and sustainable, ethical finances.

Annual Infrastructure emissions remain stable for UK citizens at 2.75 tCO2e/Year but personally Offset by 42% or 1.15 tCO2e/Year, through natural sequestration by tree planting.

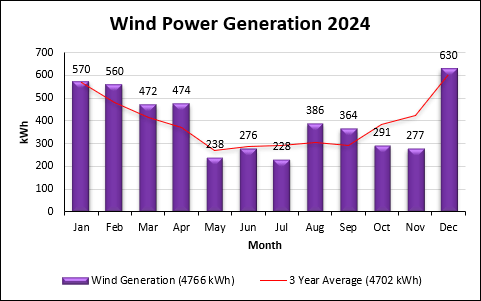

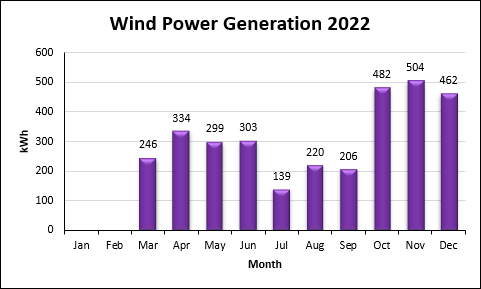

Renewable power generation from a share in the Ripple Energy Graig Fatha Wind Turbine project, the UK’s first consumer-owned renewable energy generation source, displaces fossil-fuel generated emissions from the National Grid. In 2024, this removed 1.1 tCO2e emissions providing off-set for 92% of emissions from my grid electricity use.

Current Specifications

- 2.8 kWp Solar power generation

- Tesla Powerwall 3, 13.5 kWh Electrical energy storage battery (Lithium Iron Phosphate).

- Efficient A-rated electrical appliances

- LED lighting in 100% of outlets

- 100% green energy supplier Octopus Energy

- Time-of-use (ToU) electricity tariff (5hrs super cheap off-peak night rate)

- Electrical energy monitoring system (OpenEnergyMonitor)

- Renewable power generation from a share in the Ripple Energy Graig Fatha Wind Turbine project.

- 300 mm Wool Fibre Loft Insulation, Cavity wall insulation, Insulated Front door (no letterbox), Insulated flat roof.

- Double glazed windows, A-rated, argon-filled, with a low emissivity coating.

- Plantation Shutters on South-East windows.

- Main Space & Water Heating –5 kW Mitsubishi Ecodan Air-source Heat Pump.

- Electric Vehicle (350-mile range on one full charge), with smart charging point at the dwelling (can charge on super off-peak rate and solar power).

- Water harvesting and Sustainable drainage system (SuDS) on driveway.

- Biodiversity enhancement through an annual donation to the Woodland Trust to plant 25 m2 of woodland, 14 native trees planted on-site, two ponds created, a green wall, and an Extensive Sedum Green Roof on flat roof extension.

Supporting Environmental Charities

- Greenpeace

- Friends of the Earth

- RSPB

- Woodland Trust

- Centre for Alternative Technology

- North Wales Wildlife Trust

- WWF

- Ethical Consumer

Green Financing

Referral Codes

Octopus Energy Referral code worth £50, https://share.octopus.energy/oak-moose-437

Ripple Energy Referral code worth £25, https://rippleenergy.com?ogu=319&rtrfn=Paul-M

In Collaboration with –

The author is a graduate of both The Open University and The Centre for Alternative Technology, and co-founder and a director of The Electric Vehicle Association in Wales EVA Cymru, a non-profit organisation. This Net-zero carbon home is part of the National Energy Foundation SuperHomes Network, and has been used as a case study in course materials for The Open University in 2024.

References

WWF, 2025. Footprint Calculator. Available at: https://footprint.wwf.org.uk/ (Accessed 16 January 2025).

WWF, 2023. Footprint Calculator Report. Available at: https://www.wwf.org.uk/our-reports/footprint-calculator-report-2023 (Accessed 16 January 2025).